适用于公寓平面图如何分布、其各部分如何安排的建筑分类通常被称为住房类型学:它定义和编目了共同的特征或类型。在建筑学中,特别是在专门用于居住的空间:公寓、房屋中,这个概念是相当有名的。

The architectural classification that is applied to how an apartment plan is distributed, how its parts are arranged is frequently referred to as housing typology: it defines and catalogs common characteristics or types. It is quite well known the concept in architecture, and particularly in spaces dedicated to inhabitation: apartments, houses.

类型学通常反映在平面模型中,与房间分布模式的迭代。

Typologies are usually reflected in plan models, with iterations of room distribution patterns.

不可避免的是,为了将某种类型的规划应用于特定的情况或背景,人们需要决定(在极少数情况下)或继承(在大多数情况下)它所对应的是哪种生活。 这时,这项工作就变得相当棘手。规范和规章制度决定了我们如何进入住房类型,它们是用某些关于家庭可能是什么以及家庭在其私密空间中应该如何行事的概念编造出来的。文化习惯带来了关于一个家庭应该是怎样的,以及如何假设它将占据房屋空间的惯例。

Inevitably, in order to apply a certain type of plan to a given situation or context, one needs to decide (in rare cases) or inherit (in most cases) to which kind of living it corresponds. At this point, the exercise becomes quite thorny. Norms and regulations dictate how we navigate into housing typologies and they are fabricated using certain notions of what a household might be and how it should behave in its intimate space. Cultural habits bring in conventions regarding how a family is supposed to look like, and how it is assumed that it will occupy the house spaces.

因此,可能性的目录大大减少了,因为,毫不奇怪,传统的家庭套件包括一个异性丈夫、妻子和一两个孩子,亲密空间从更 “公共 “的餐厅到更私密的父母房间的浴室。

在我们身边的公寓和房子中,属于这种难以质疑的模式的比例最大。

Thus, the catalog of possibilities is drastically reduced since, unsurprisingly, the household traditional kit of parts comprehends a heterosexual husband, wife, and one or two kids with intimacy spaces ranging from the more “public” as the dining room to the more private as the parents’ room bathroom.

The greatest percentage of apartments and houses around us belong to this hard-to-question model.

2018年,苹果公司推出了memojis,比他的亚洲竞争对手落后一些,但外观更性感。memojis通过追踪我们的面部动作来创建我们自己的头像。这个想法是,这个虚拟人物将逐步学习如何创建一个情感手势的目录,这将具体定义我们的数字自我。正如Shoshana Zuboff在她关于监控资本主义的大量研究中所揭露的那样,这种变态来自于一个持续的反向运动:为我们的头像提供一系列可分类的情感面部手势,我们以某种方式将这些手势屈从于应用的技术限制。这种在我们的脸和手机屏幕之间的来回穿梭,模糊了我们的指挥权,以至于我们可能永远都不会真正知道,我们是否已经告知了阿凡达关于我们面部情感的可能性,或者它的技术能力是否已经制约了我们的微笑。

In 2018 Apple came up with the memojis, a bit behind his Asian competitors but in a sexier look. Memojis create avatar of ourselves by tracking our facial movements. The idea is that this avatar will learn progressively how to create a catalog of emotional gestures that would specifically define our digital self. The perversion comes, as Shoshana Zuboff has exposed in her extensive research on Surveillance Capitalism, from a continuously reversed movement: providing our avatar with a series of classifiable emotional facial gestures, we somehow subjugate these gestures to the technological limitations of the app. This going back and forth between our face and the phone screen blurs our power of command to a point where we will probably never really know if we have informed the avatar about our facial emotional possibilities or if its technological capacities have conditioned our smiles.

我想,这同样适用于我们空间的类型化调节。我们永远不知道是谁在指挥。但我们确实知道,作为建筑师、设计师,这些条件不考虑多样性。我们被迫工作,好像每一个空间都是针对一类非性别的、单一的家庭。因此,谁在设计我们的生活空间?强加在住房类型上的未言明的价值是什么?在我们的房屋中,是否有同伴物种的空间?一个人的公寓和一个四口之家的公寓是否有相同的空间组织?它是否允许挪用?灵活使用吗?当代家庭的需求和过去一样吗?

I guess that the same applies to the typological conditioning of our spaces. We will never know who is at command. But we do know, as architects, designers, that these conditions do not consider diversity. We are forced to work as if every space was addressed to one single category of non-gendered, monolithic households. Who is thus designing our living spaces? What are the unsaid values imposed on housing typologies? Is there space, in our houses, for companion-species? Does an apartment for a single person respond to the same space organization as one for a family of four? Does it allow appropriation? Flexibility in use? Are the needs of a contemporary family the same as in the past?

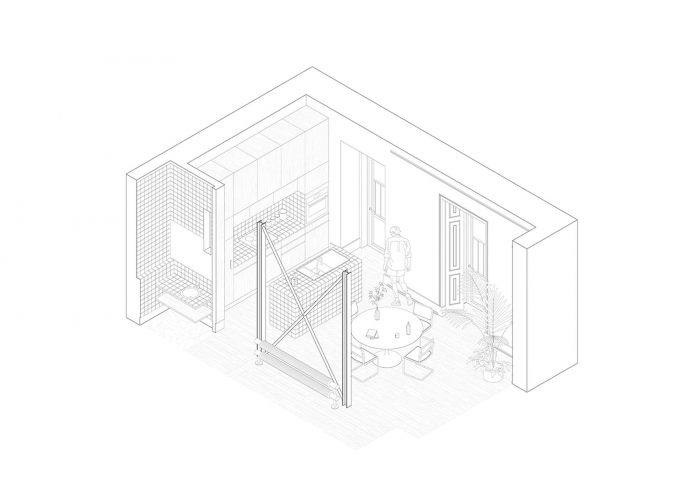

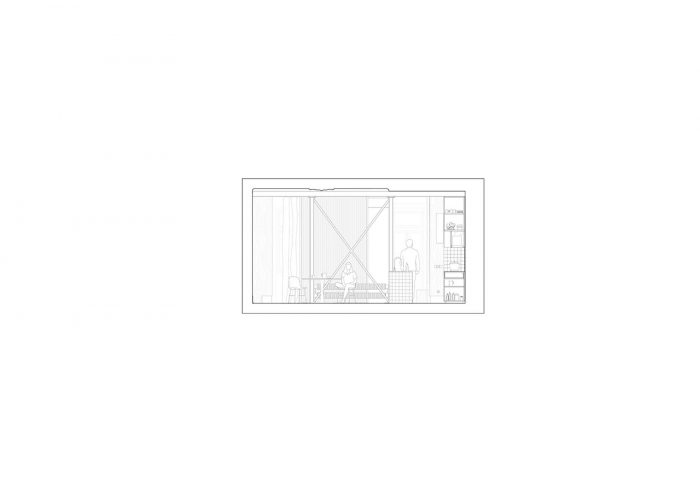

MARIA只是一个公寓,一个居住者的地方,她有可能永远睡在沙发上,和狗住在一起,在阳台上做饭,在地板上吃饭,在浴室里看书,站在厨房的台子上,她决定不需要对自己多种多样、丰富多样的日常姿态和使用仪式进行编目,创造一个自己的头像。MARIA是一个断断续续的物理空间,等待着以最丰富的方式被居住,没有偏见和定向的居住方式。作为空间,MARIA有一个未被定义的性身份。

MARIA is just an apartment, a place for an occupant that can potentially always sleep on a couch, live with a dog, cook on the balcony, eat on the floor, read in the bathroom, stand on the kitchen counter, and decide that she does not need to catalog her multiple, rich and diverse everyday gestures and usage rituals to create an avatar of herself. MARIA is a disconnected physical space waiting to be inhabited in the richest way possible, without prejudices and directed ways of inhabitation. As space, MARIA has an undefined sexual identity.

建筑师:Daniel Zamarbide

面积: 88 m²

年份:2020年

摄影:Francisco Nogueira

项目团队:Daniel Zamarbide, Carine Pimenta, Galliane Zamarbide

概念设计:Daniel Zamarbide, João Paixão, Carine Pimenta, Francisco Castelo Branco

施工图:Carine Pimenta, Jolan Haidinger, Tobias Vonder Mühll

施工监理:Carine Pimenta, Jolan Haidinger

出版画册:Driss Veyry

城市:里斯本

国家:葡萄牙

Architects: Daniel Zamarbide

Area: 88 m²

Year: 2020

Photographs: Francisco Nogueira

Project Team:Daniel Zamarbide, Carine Pimenta, Galliane Zamarbide

Concept Design :Daniel Zamarbide, João Paixão, Carine Pimenta, Francisco Castelo Branco

Construction Drawings :Carine Pimenta, Jolan Haidinger, Tobias Vonder Mühll

Construction Supervision :Carine Pimenta, Jolan Haidinger

Publication Drawings :Driss Veyry

City:Lisbon

Country:Portugal